“Now and Then With Justin Kantor” is a new SoulTracks feature where we have an in depth conversation with a classic soul star about his or her career, including what’s happening now. Noted soul music writer Justin Kantor is our guide bringing SoulTrackers up to date on their favorite stars. Do you have ideas for future “Now and Then” features? You can connect with Justin on Twitter. And let us know what you think!

“Now and Then With Justin Kantor” is a new SoulTracks feature where we have an in depth conversation with a classic soul star about his or her career, including what’s happening now. Noted soul music writer Justin Kantor is our guide bringing SoulTrackers up to date on their favorite stars. Do you have ideas for future “Now and Then” features? You can connect with Justin on Twitter. And let us know what you think!

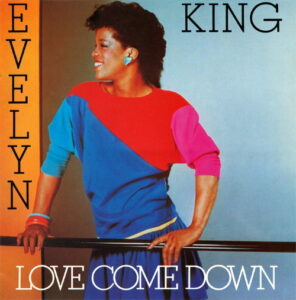

Throughout the 1980s, Kashif made an indelible impact on soul-music audiences as a producer, songwriter, singer, and musician. With both his own hits—“Are You the Woman,” “Baby Don’t Break Your Baby’s Heart,” and “Say Something Love,”—and his unforgettable contributions to the recorded legacies of Whitney Houston (“You Give Good Love”), Melba Moore (“Love’s Comin’ at Ya”), and Evelyn “Champagne” King (“Love Come Down”), he blazed powerful sonic trails in R&B with his expert fusion of progressive synthesizer grooves, jazz-steeped arrangements, and multi-layered vocal methodologies. During the ‘90s, he demonstrated his expertise as an industry insider with his book, Everything You’d Better Know about the Record Industry. Although he’s been largely out of the public eye for the past decade, he’s been keeping busy with a variety of endeavors. Filling readers in on those pursuits, as well as his multi-tiered artistic progression up to the present, he speaks with Justin Kantor for the latest installment of Soul Tracks’ Now and Then.

You’re producing a documentary called The History of R&B Music and Its Influence on World Culture. Tell me about that.

We start from Africa. When you talk about rhythm, that’s where it comes from. We move forward to rural southern USA, where the more vocal utterances of the slaves as they worked in the fields were used as a form of communication. That goes into gospel music, the Delta blues, and Chicago blues. We come forward all the way to today. There’s been a lot of great R&B music.

You might ask, “What has it influenced?” Take a song like “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud” by James Brown from 1968. That came right in the middle of the Civil Rights movement. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., had been killed in April of that year. There was an uproar. The American government and media were having a very open, vivid conversation about what we should call black people. “Should we call them black? Africans? African descendents? African-Americans?” Ironically, if you called us black, we didn’t like that. It was an insult. One week, you call me “black” and we’re fighting like two junkmen on the street. Then, James Brown recorded that song in August, 1968. After it was released, if you called me black, I’d put my hands on my hips and wear my ethnicity as a badge of honor. How much did that change the trajectory of the universe as a whole?

That’s what this ten-part series is about: the impact that rhythm and blues music has had on people all over the world. People like Patti LaBelle. When she recorded “New Attitude,” every woman within earshot of a radio got a new attitude whether she needed one or not!

Is the documentary comprised of historical clips, or new interviews with artists?

Both. We use historical clips. We use interviews that we’re going out and filming ourselves in 18 cities on four different continents. We’re using archive articles and photographs, too.

How are you planning on distributing it?

A limited theatrical release might take place through film festivals. But being a ten-part series, it’s for television and the Internet We have our eye on some networks; but we’re not going to make that decision until we’re finished. The important thing is that whatever network we go to give it the appropriate marketing and promote it in a way that allows us to reach as many people as possible.

Was there a personal happening that inspired you to start this documentary?

It was something outside of myself. I’ve always lived at the intersection of art and education. Throughout my career, I’ve been involved in educational projects and many artistic endeavors. My favorite documentarian of this time is Ken Burns. He did the Jazz documentary series. I felt that in order for rhythm and blues music to achieve its proper perspective in the minds of people all over the world, we had to capsulate it in the form of a project that tells the stories accurately. They’ve done it for rock and roll, jazz, and classical. Certainly, it should be done for R&B.

Being a ten-part documentary, does each part focus on a specific era of R&B? Could someone just watch one part and get the gist?

Each one will be a complete story within itself. We’re encouraging everyone to see all the parts. We’ve broken it down to subjects such as “Divas on the Rise,” “The Bad Boys of R&B,” “The Hitmakers,” and “On the Radio.” I think that a chronological format would prohibit the viewing of younger people, who tend to not delve into history as much as people from back in the day.

I grew up in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. In New York, there’s a lot of culture and support for the arts. It’s a hodge-podge of different types of artistic expression. My friends in New York are comprised of playwrights, dancers, orchestra folks, players in jazz bands. In my neighborhood, they had a jazz mobile. As a kid, this truck would come up and open the side, and there sat Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Eubie Blake, who lived two blocks away from me! I got to sit on his lap while he played piano. That was very impactful.

What I also remember about that time is that we played music for the sake of playing music. As we matured and started playing in neighborhood bands, the whole thing for us about it was nailing it and blowing everybody’s tops off [with our musicianship]. We didn’t play music from a perspective of making money—although that occurred to us later, thankfully! It was really about our skill level: could we play a Herbie Hancock solo like he played it without flubbing it up? That’s very different from what I see today in pop music, for the most part. People seem to enter the business for the purpose of making lots of money and having that money prove that they’re better than everybody else.

What was your first instrument?

Trumpet, then flute. A junior high school instructor, Mr. Robert Wedlaw, became my mentor. He’d come to my house at 6:30 in the morning, because I lived across the street from the school. He’d take me into the class and teach me every instrument in the orchestra. Sometimes within the course of a week, he’d give me three different instruments. Like, “Here’s a violin. Go home and learn how to play the C-scale.” I’d come back and eek it out. The next day, he’d say, “Here’s a tenor saxophone.” He wanted me to understand from a very organic perspective the different timbres that those instruments could make. He knew if he gave me those instruments, I’d begin to pay attention to them as they were employed on television, in recordings, and in movies. I could tune into them and the roles they were playing in the orchestra.

One of the earliest professional experiences that the public became familiar with your work through was your role as a keyboardist in B.T. Express, beginning with the Energy to Burn album. You also wrote the song, “Sunshine,” for the group. How did you come to be a part of an established group like that? What would you say you added to their sound?

I was inducted into B.T. Express on the efforts of a woman named Sandy Davis. She was the daughter of King Davis, who was the group’s manager. I went to high school with Sandy, and she told her father that she knew me. She said I was a good singer and keyboardist and that he should put me in the group. He was crazy enough to listen to her [laughs]. That was the second most influential thing that happened to me, after having Mr. Wedlaw as my junior high school mentor.

I brought a more sophisticated sound to the group. They were heavily into funk and dance music at the time. My influences were very much based in jazz and classical. I brought more chord changes when they would hang on that minor chord. It was a really important time in my life. It gave me a focus on songwriting. I began to understand how songs are chosen that are appropriate for a particular band or artist. It also made me pay more attention to melodies and how they would fit in a particular genre.

During that time, you changed your name to Kashif. What inspired that?

I had two mentors in that group. Carlos Ward, who played alto sax and flute, really pushed me into jazz. He introduced me to [the works of] McCoy Tyner and Art Tatum. Then, there was Jamal Rasool [originally known as Louis Risbrook], who was the bass player. He was very disciplined with his life. I looked up to him. He practiced all the time. He was teaching himself how to speak Arabic. He was a Muslim. I said, “If this cat is this cool, I wanna know some of what he knows.” I hung close to him. He gave me a book of Islamic names. At that time, I was about 15. I was really focusing on my spiritual growth and learning about different religions. I looked in the book, thinking, “This is a crazy industry. What name can I choose that when it’s spoken, I’m always reminded of what my goals are in life?” Kashif means discoverer, inventor, and magic-maker. Saleem, my last name, means one who comes in peace.

What prompted you to leave the group after several albums?

I was a bit of a nuisance. I was always pushing the band: let’s write some better songs and focus on our craft a bit more. They were riding the wave of being very popular. They had more girls than they could ever get to! I pressured them. They got together one day and said, “If you’re unhappy, we’re firing you from the band.” They got together with their new manager at the time, Norby Walters, who was working with King Davis. He was the most prominent and influential booking agent for black acts in the world. Nobody could touch him, because he understood the art form and respected the artists.

We were in a meeting with Norby when he had just become co-manager. Everybody got up to leave after they fired me. He asked me to come back into his office. He asked me what I wanted to do. I said that I wanted to write great songs and produce great music. “I’m tired of this marginal stuff we’re making. We can compete with Earth, Wind & Fire and Kool & The Gang.” He asked me what equipment I owned. I had an electric piano and a moog synthesizer. He asked to hear some of my music. I gave him a cassette. He put it in and said there was a studio in Manhattan called Opal. He said he would pay for some studio time for me to go in and write some music and do whatever I wanted to do! Of course, I made use of it.

You started doing a little writing for other acts while you were in B.T. Express. For example, “Get out on the Dance Floor” for Fatback. Had you started shopping your songs to different artists?

Actually, one of Bill Curtis’s dancers was a good friend of mine. She played some of my stuff for him. He asked her to bring me down.

1981 was a big year for you. Was it through the experience of being in the studio that you got the connections to pitch your songs to other artists?

As a result of Evelyn King’s “I’m in Love” coming out and it having a new sound, I got a lot of calls from other producers to participate. I was always in the studio. Just before that time, I was playing keyboards in Stephanie Mills’ touring band. I was also a New York session player. I played on records by Aretha Franklin, Peabo Bryson, and the Rolling Stones. I worked as a session singer, as well, with top singers like Luther Vandross, Tawatha Agee, and Brenda White. Somedays, I’d have several sessions as a keyboardist and another couple as a background singer. Being around all of those great singers honed my skills vocally. The challenge of walking into a session and not knowing what I was going to find as a keyboard player—on Hall & Oates, for example—allowed me to observe what all those great producers’ methodologies were.

.