Raphael Saadiq – Jimmy Lee

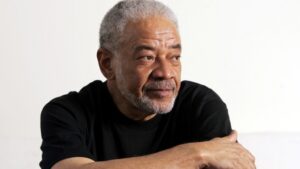

Longtime fans of neo-soul groundbreaker Raphael Saadiq are in for an unexpected, decidedly dark ride with the arrival of his first album in nearly a decade, Jimmy Lee. The one-time Tony Toni Tone’ frontman built a reputation throughout the 2000s and early 2010s as a masterful purveyor of grown folks’ R&B blending equal parts classic soul, bluesy strains, hip-hop finesse, and rock influences. That’s not all cast aside on his fifth solo set to date; but the core subject matter at hand here inevitably drives the material in a more intense, often starkly different musical direction than that found on previous sets like The Way I See It and Stone Rollin’.

A chance for Saadiq to convey the tragic stories and fates of family members lost to drugs, violence, and social injustice, Jimmy Lee emerges as a straightforwardly complex—and ultimately, disturbingly truthful—commentary on the woes of racial inequality, personal addiction, and an unforgiving criminal justice system. This is evident from the outset, as he imparts on “Sinner’s Prayer”: “Our baby daughter may not see five/This kind of hurt can’t be justified.” The mournful guitar strains interspersed through the thick undercurrent of still keyboard passages make clear the cries, “God, when the sinner is praying/God, do you still hear it…Help me make it.”

Most of the songs on Jimmy Lee end cold with a radio tuning effect quickly giving way to the next chapter. The uptempo funk groove of “So Ready” may momentarily suggest that a party’s about to start, but the story line is in keeping with the internal and external demons referenced in “Sinner’s Prayer.” Saadiq’s character confesses with alternating conviction and resignation, “I’m still out here living wrong, these drugs was too strong/And then I broke your heart, my friend.” The crisp hip-hop drumming of Lemar Carter, laced with Dylan Wiggins’ enigmatic piano nuances, provides a sturdy and engaging platform for the reflection and despair of “The World Is Drunk,” while Saadiq’s own percussive abilities drive the first single, “Something Keeps Calling.” Echoing the chord structure of The Isley Brothers’ “Footsteps in the Dark,” the midtempo selection’s first-person narrative wrestles with questions at large symptomatic of hopelessness and addiction. There are brief hints at tiny traces of hope, but the lingering burden of feeling lesser than won’t hang up.

A concentrated clash of grunge guitars and flurries of woodwinds over aggressive drums back Jimmy Lee’s plunge into the bleak, daily life-altering effects of chemical dependency on “Kings Fall,” while the cymbal crashes and repeated hums of “love, love, love, love, love…” crystallize the imagined happiness it brings on “I’m Feeling Love.” Many singer-songwriters make questionable claims of staying artistically true to themselves; but by the halfway point of Jimmy Lee, it’s clear that Saadiq is genuine in his stated mission to make music first and foremost for himself. There are no stabs at radio-ready fare or cash-grab elements to make the darkness of the album more palatable for listeners unfamiliar with his history. It is a true process of attempting catharsis through blunt artistry.

Respected rappers have frequently explored the murky, entangled worlds of discrimination, poverty, and drug-dealing—and the mental and emotional suicide in which they prevalently result. Far fewer singers, however, have delved as deeply into that universe to construct an album’s worth of connected plots and character studies on the subject as Saadiq does on Jimmy Lee. His eclectic production sensibilities and well-honed skills on multiple instruments further enable him to convey the muddled existence and grave reality resulting from the circumstances related in the stories.

Thematically, the second half of Jimmy Lee progresses into the sometimes more obscured aspects of coping with and denial of the altered states brought about by the demons Saadiq sings about in earlier cuts. Musically, the vibe becomes accordingly more dissonant, as on “My Walk,” a sort of “Walk on the Wild Side”-meets-spaced-out-minimalism. The contrast of coarse drum patterns to his gospel-like backing refrains drives home the passages’ unsettling confessions. Ever the prolific producer for fellow artists, he relinquishes the vocal spotlight to Reverend Elijah Baker for the surprising straight-ahead down-home gospel of “Belongs to God,” the set’s one untarnished hint of salvation.

The tumultuous path of Jimmy Lee thickens on the cautionary mind-warp of “Glory to the Veins,” while the unhappy ending for many in his shoes is exposed on “Rikers Island.” This lament to the infamous jail complex in New York’s East River is embedded with a spiritual feel in Saadiq’s hook vocals multi-tracked many times over to resemble a choir, while Kelvin Wooten’s piano and B3 organ fills boost the underlying urgency of the story: “The boy is shaking inside/He says it’s something he didn’t do/He’s afraid to take that long ride/Down Rikers Avenue.” It’s followed by a striking spoken-word “redux” performed by actor Daniel J. Watts, with Saadiq’s pensive guitar work and vocal phrases adding momentum to his striking parlance and societal wake-up call.

The closing track of Jimmy Lee, fronted by rapper Kendrick Lamar, is one of the set’s most impactful moments in its inconclusiveness. The solid groove and easy guitar licks are juxtaposed with Saadiq’s glum baritone delivery of the chorus: “I thank God for giving us this life/The day you’re born, someone else dies/All in love, all is in life/Your life is in your rearview.”

In today’s overwhelmingly troubled times, the edgy, genre-bending arrangements and production of Jimmy Lee may be hard to appreciate given the harsh realities brought to the surface in the unconcealed storylines. Saadiq’s delivery, however, ensures that they are presented in an at once practical and creative flow that just might make a bit of a difference for someone lingering on the edge. Recommended.