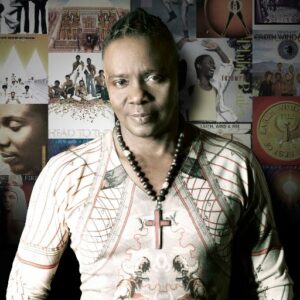

(April 10, 2018) There were few acts who better bridged the world of Gospel and R&B music than The Staples Singers did in the 1970s. A family act in the truest sense of the word, they anointed their listeners while also delivering a groove, and in the process helped open the door for hundreds of subsequent artists. We are sad to report that Yvonne Staples, whose deep rich voice anchored many of the group’s legendary harmonies, has died at age 80.

Yvonne, along with her singing siblings Mavis and Cleo, and her father Roebuck, better known as “Pops,” came a long way from their native Mississippi, traveling a long, artistically-rich road into the mainstream of American music.

Roebuck Staples was born in 1915 in Winona, Mississippi, where he grew up with hard times and the blues, his singing and guitar style influenced by country bluesmen Barbecue Bob and Big Bill Broonzy. But Roebuck found the Lord and joined a jubilee quartet called the Golden Trumpets. Roebuck, his wife Oceola, and their two children, Cleotha and Pervis, moved north to Chicago in 1936, where Yvonne and Mavis were born a few years later.

Singing in a Southern quartet style usually performed by all-male, adult groups, the Staples Singers began appearing at local churches in 1948. Mavis, then age seven, handled the bass parts. By 1954, Pops, Mavis, Cleo, and Pervis (Yvonne replaced him many years later) landed a contract with Chicago’s United label, cutting a number called “Sit Down Servant.” Pop’s thin, winsome tenor shared the lead with Mavis’s deep, throaty tones, although her unique contralto had not developed the emotional edge it was soon to have. The record failed to catch on, though, perhaps because Pops’ reverberating down-home guitar, which would become another trademark of their style, was overshadowed by a rinky-tink piano.

The Staples sound did click in a big way when their haunting 1957 Vee-Jay recording of “Uncloudy Day” became a nationwide gospel hit. Others followed, including “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” “Help Me, Jesus,” and “Swing Down Chariot (Let Me Ride”), established the Staples as one of America’s top gospel attractions. They were signed to Bill Grauer and Orrin Keepnews’s Riverside jazz label in 1962 when the folk music boom was in full force. The group was beginning to pick up college bookings, in addition to their religious dates. While at Riverside, they were the first black artists to record material by Bob Dylan.

Their following continued to expand when they moved to the Epic label, where they became identified with social protest songs like “Freedom Highway” and “Why? (Am I Treated So Bad),” both penned by Pops, and Stephen Stills’s “For What It’s Worth.” (The latter two were produced by rock and roll legend Larry Williams.)

When the Staples joined Stax in 1968, they were working alongside major rock acts at places like the Fillmore West and East. The first two Stax albums, produced by Steve Cropper, continued in the folk vein, but their third, The Staple Swingers, offered a bold new direction of hip soul “message” songs. It was produced in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, by Al Bell, as was their next, Be Altitude: Respect Yourself. Be Altitude broke the Staples Singers wide open. “Respect Yourself,” written by Mack Rice and Luther Ingram, reached the Number Two position on Billboard‘s soul chart, while Al Bell’s “I’ll Take You There,” with its infectious reggae-like beat, hit Number One soul and pop.

There were more hits at Stax-“Oh La De Da,” “If You’re Ready (Come Go with Me),” and “Touch a Hand, Make a Friend”-before they moved on to Warner Bros., where they scored with Curtis Mayfield’s soundtrack to Let’s Do It Again.

The group continued to perform with success for years to come, and sister Mavis developed a following as a solo singer. Yvonne Staples continued to sing in various capacities, but had already made for herself a permanent mark in the history of popular music.